the 5 main causes of back pain

Let’s debunk common back pain myths

-

You can’t diagnose lower back pain

-

Back pain goes away quickly

These myths have lead to back pain being ignored as an important problem as the prevailing attitude has been “You can’t diagnose it, and it will go away anyway, so don’t worry, you’ll be OK”. My kids would refer to this as an “internet fact” not a “true fact”. Eighty percent of people will suffer lower back pain at some time in their life. Although, the minority (20%) recover fully, most (80%) of people still complain of pain at 12 months. Fifty-five percent suffer low grade pain, 15% moderate levels and 10% are significantly disabled (Von Korff M, Saunders K. Spine 1996). Said differently, at some time in your life you are likely to suffer back pain that lasts for 12 months, or longer. The diagnosis of the cause of lower back pain is also now possible in most cases. “Non-specific lower back pain” is no longer “Non-specific”.

There are 5 main causes of lower back pain;

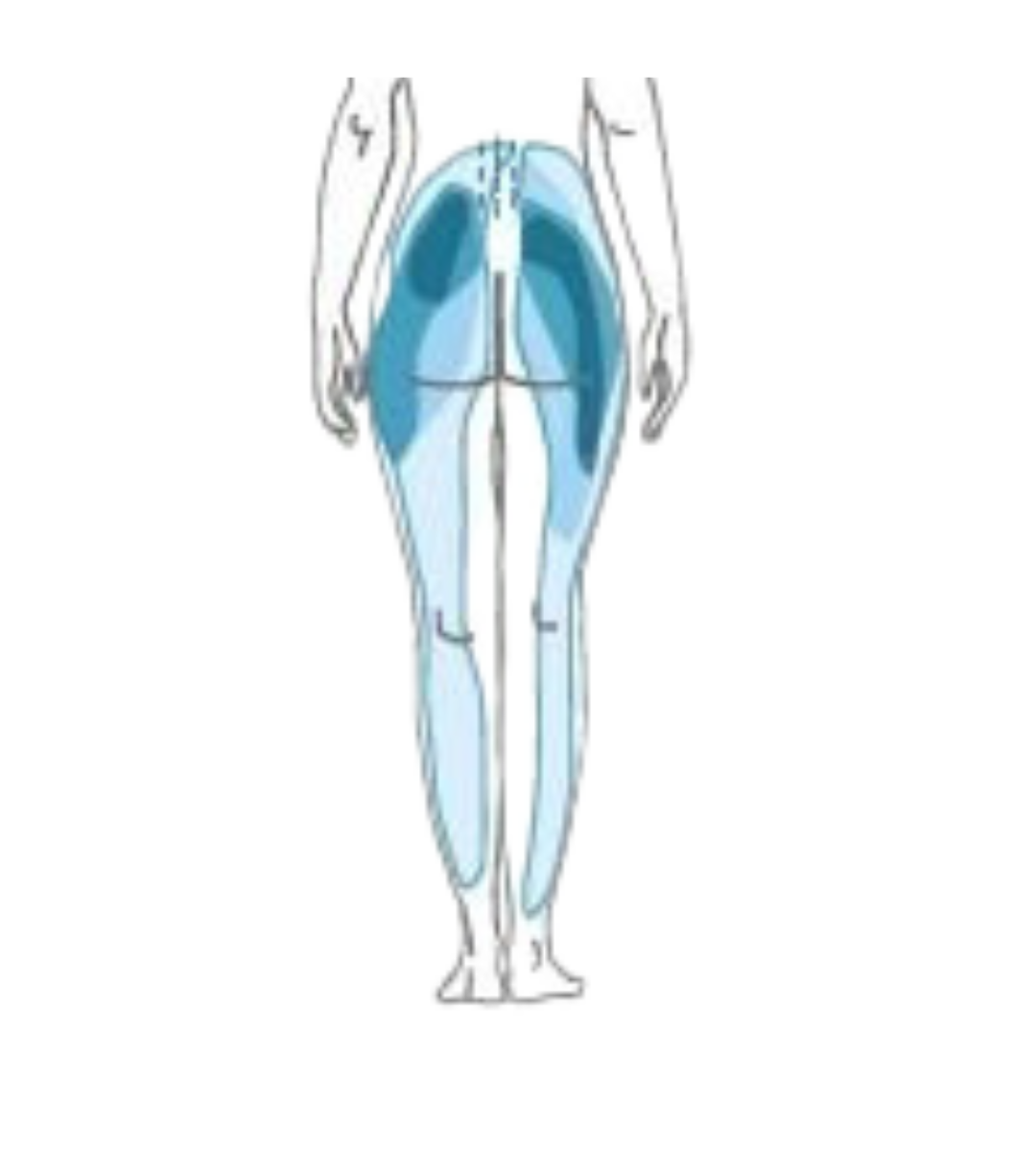

To help identify which one is the primary cause of pain, we utilise a range of standard questions like what triggered it, where it’s located, where is radiates, what makes it better or worse and any associated symptoms to try pin down which one is the culprit. Unfortunately, many of the answers are not specific for one structure and if the patient is in a lot of pain, everything hurts. Below is a picture of the referral patterns of sources of lower back pain - sacroiliac joint (yellow), facet joint (blue), hip (purple), disc (green) and nerve root pain (orange). As you can see they all overlap, making it difficult to identify pain simply based on where its felt.

In this situation, you would think a scan may be of use. Unfortunately, this is commonly not the case. For lower backs, 83% of people with NO PAIN will have a disc degeneration, a bulge, protrusion or extrusion. With a range of other changes just being “wrinkles” on a scan. The picture below gives you an idea of what is “normal” on a back MRI.

Because what the pain feels like, where it radiates and scans are not very accurate at diagnosing pain. The way to diagnose lower back pain is to block or “numb up” specific structures or their nerve supply, and see if the pain goes away. This is done in a step by step fashion starting with the most likely structure based on history, examination and imaging findings. Numbing up the area is commonly done twice with different local anaesthetics to confirm the pain actually goes away. If done is this way, 85% of the origin of pain can be identified.

The big 5

Facet joint pain

The first of the “Big 5” is facet joint pain. The facet joints sit at the back part of the spinal column and are the source of back pain in at least 30% of people. When people speak about having arthritis in their back, this is probably the part that is affected. However, arthritis in backs is common and in most cases doesn’t actually hurt. As you get older is it more likely back pain is coming from facet joints, however, on MRI’s of people with NO PAIN at age 80, 83% of people have facet joint arthritis. So just because it is on the scan, doesn’t mean it hurts.

Symptoms

The symptoms of facet joint pain are non-specific and overlap with other structures from the back. As a rule of thumb, the pain is an ache above the belt line, tennis ball or larger in size, and commonly more to one side or the other. It can radiate down the leg as far as the calf and very regularly gets labelled as “Sciatica”, but is it not. The pain is generally worse with bending backwards, and in the morning is associated with stiffness that improves as you warm up over 10-30 minutes. If you are being examined by a doctor they may try to reproduce you pain by pushing over the facets and doing a test called the Quadrant Test. This is done by bending backwards and to toward the side of pain, trying to reproduce the “usual” pain. Interestingly, if you have no pain when doing this it makes it unlikely the pain is coming from your facets.

Confirming that facets are the source of the pain is done either with facet joint injection or by blocking the nerves that supply the facets. This is known as a medial branch block. Although, you would think injecting the facet directly would be a good test, it turns out it isn’t because of leakage out of the joint. As a result we tend to avoid these and perform medial branch blocks. Medial Branch blocks use a very small amount of local anaesthetic to numb the nerves that supply the joints. It is performed on 2 separate occasions and if the pain goes away both occasions, it is highly likely the facets are responsible for the pain.

Treatment

To be able to “fix” the joint would be great, but at the moment, there is no such solution. Treatment is aimed at decreasing the pain arising from the joints rather than “fixing” them. This is done utilising multiple techniques including medications, rehab and exercise. In addition, the pain signal can be disrupted from getting from the facet joint to your brain by a process known as radiofrequency ablation. This process heats the same nerves we blocked during medial branch blocks. Radiofrequency ablation is effective in 60-90% of people, and results in 60-90% decrease in pain for 9 -18 months. In many people, when the nerve regenerates the pain does not return, however if it does, it can be repeated with expectation of getting a similar period of pain relief. With regards to stem cells, there has been some anecdotal reports in the media about their success, but nothing published to my knowledge in the scientific literature. It is certainly an area that may be effective and we will likely be looking at a study using cells in people with confirmed facet joint pain that have failed normal treatment, in the future.

Sacroiliac joint pain (SIJ)

Sacroiliac joints are just below the facet joints. They are the joint that connects your back to your legs and move very little. About 15-30% of back pain is said to arise from sacroiliac joints but it gets more common as patients get older (Schwarzer et al, 1995, Dreyfuss et al, 2004, Rathmell 2008, Depalmer et al, 2011).

The pain of sacroiliac joints is similar to that of other structures in the back. The pain is a deep ache through to sharp pain. It rarely goes above the belt line (Dreyfuss, et al, 2004b) and refers to both buttocks (94%), thigh (50%), calf (28%) and foot (14%) (Slipman et al, 2000). A golf ball sized area of pain over the SIJ and just below the posterior superior iliac spine (“bony bit” at the back) that contains the majority of their pain, indicates the SIJ may be the source of pain (Dreyfuss, et al, 2004b). Asking the patient to point to the majority of the pain with one finger can also be very helpful (fortein ref).

The pain is generally worse with sitting, moving from sitting to standing, lying flat and rolling over in bed and going down stairs. There are a range of tests used to examine the sacroiliac joint, no one of them is truly effective at confirming the diagnosis and they need to be used together to add to the whole picture (ref). Scans are not useful, unless an inflammatory arthritis, such as ankylosing spondylitis is suspected.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is once again done by numbing up the joint. This can be done in a similar fashion to facets by either injecting the joint or blocking the nerves that supply the joint. There is argument whether one way of the other is more effective and both may be used on separate occasions to confirm the SIJ is the source of pain.

In addition to the SIJ being painful it may also be loose. This is a controversial area and many clinicians will disagree that the SIJ can move or be loose. I likely have a biased population of patients that do appear to have SIJ laxity or pelvic instability, who improve when it is treated, so I am in the group of clinicians that think the condition exists.

Pelvic instability occurs as a result of the pelvis being excessively mobile, or “hyper”-mobile. The classical presentation is the after child birth. Pelvic hypermobility arises due to loosening of the ligaments during pregnancy in preparation for birth of the child. Once the baby is born, hormone levels drop and ligaments should stiffen back up. However, is some women this doesn’t happen, and they might develop significant SIJ or pubic symphysis pain. This is commonly accompanied by a sense of weakness and muscle tightness about the pelvis. The weakness occurs because as the muscles attempt to contract, the pelvis shifts, thus they don’t contract effectively and feel “weak”. The tightness arises as the muscles attempt to compensate for the loose ligaments, and tighten to stabilise the pelvis. In the setting of having babies the ligament laxity and pelvic instability makes sense, and it is quite well accepted and treated. For those not pregnant people, pelvic instability due to ligament laxity is harder to grasp. I see ligament laxity as being on a continuum from “stiff” to “hypermobile”. Those who are on the “stiff” end of the continuum tend not to have issues with pelvic instability, unless they have suffered a fall. The classic is “I fell down some stairs and landed on my bum”. This can result in a fracture of the pelvis or the SIJ being subluxed and becoming unstable. At the other end of the continuum are those that are “hypermobile”. These people generally do well in sports such as dancing or gymnastics that require a large degree of flexibility. The down side is they tend to have ligaments that are closer to those of pregnant women, and so, suffer more frequently with pain related to pelvic instability.

Some anecdotal hints that pelvic instability may be playing a role. The pain is below the belt line over the buttock, with associated pain over the outside parts of the hips (commonly incorrectly labelled as bursitis) and pain over pubic symphysis. There tends to be a sense of muscle tightness across the buttocks and groins. The pain is better with crossing your legs and worse with rolling over in bed. As part of treating pelvic instability, many people try to do pilates to help strengthen their “core”, however, due to the loose ligaments, most people fail to progress and frequently find they get worse or flare after exercising.

Treatment

Treatment of SIJ pain is dependent on the cause. If you solely have SIJ pain that resolves with blocking the joint or the nerves that supply it, radiofrequency ablation can once again be effective. There are unfortunately no randomised control trials of SIJ radiofrequency ablation. However, there has been a large case series of 300 patients published. (Mitchell et al, 2015). This showed that 70% of people get 70-80% pain relief that lasts on average 9-18 months. For the 30% that don’t get relief, it’s probably because the diagnosis is wrong (12%) or they have nerve supply from the back and front (20%) of the joint. Unfortunately, we can’t get to nerves at the front. For the first 2 weeks after the procedure there can be some worsening of the pain, but this only last to 6 weeks in 1% of people and 6 months in 1 in 1000. This can be well managed with topical creams for the duration of pain.

If the pain is arising from the SIJ in the setting of SIJ laxity or instability, treating the instability can be an effective way of addressing the pain, but this is controversial. Simple measures include using sacroiliac joint belts and exercise that improves muscle strength about the pelvis. If this is unsuccessful, prolotherapy can be effective. Prolotherapy is the injection of concentrated glucose solution into the ligaments. This results in an inflammatory reaction and stiffening of the ligaments. It has been shown to improve function in 78% of patients (Cusi et al, BJSM 2010 and completely decrease pain in 40% of patients, significantly decrease pain in 30%, 20% have improvement by require further intervention, and 10% gain no benefit (Mitchell, et al, JSAMS 2015).

Discogenic Pain

Nerve Pain

Pain generated due to compression of a nerve root presents in 2 different ways. The 1st type of pain is an electric shock that runs from your bum and fires down the back of your leg and comes out your toes, this is known as Radicular pain. If the pain shoots out your big to it is probably L5 that is being effected, if its’ your little toe (or outside of your foot) it is likely S1. If it doesn’t make it down to your foot and stops at you shin it will probably be L4 and if stops at the inside of your knee, then L3. The second type of pain is in the same general pattern as Radicular pain but is achy rather than like an electric shock and it can be combined with burning, pins and needles, numbness or weakness of particular muscles (this is technically called a radiculopathy).

Enter the confusion. Both these types of pain are referred to as “Sciatica”. The confusion doesn’t come from radicular pain, as this is a very specific type of pain and easily diagnosed. The problem is the achy pain. All the big 5 of lower back pain can give you achy pain down your legs. This type of pain is referred to as Somatic referred pain. ‘Soma’ means body, I think of it as “pain from a body part”. The question is “Which part?” Is it facet, sacroiliac, hip, disc or nerves? Once it is labelled as sciatica, the doctor is diagnosing the pain as being caused by nerve root compression, but as multiple things cause this type of pain, this is not necessarily the case. The confusion worsens as MRI’s get added to the mix. Twenty two percent of people with no pain have nerve root compression on their scans. So just because something is on the scan, doesn’t mean it is the source of pain. A hint that somatic pain down the legs is coming from a nerve root is that the pain tends to be worse in the legs than the back, tends to be in a more specific pattern (in doctor language we refer to it as “dermatomal”) and can be associated burning, pins and needles, numbness, weakness or decreased reflexes. (You can see I am qualifying my language with these descriptions. Unfortunately, there are no hard and fast rules, working this out is not easy. If it was you probably wouldn’t be reading this).

Diagnosis

To diagnose pain arising from a nerve root we do an epidural. This is different to an epidural that we do for pain during childbirth. It is an injection targeted about the nerve root we believe is causing the pain. The epidural will include local anaesthetic and cortisone. After the injection we track what happens in the first 6 hours, and then over the next 2 weeks. During the first hours the local anaesthetic is active, if the pain goes away during this time, it gives a good indication that that nerve is responsible for the pain. We then look to see what happens over the next 2 weeks. During this period the cortisone will start to act. Cortisone decreases irritation of the nerve. Even if the nerve is compressed, removing the “irritation” that comes from the inflammation about the nerve, may be enough to decrease the pain substantially and for prolonged periods. As we noted above, 20% of people have compressed nerves on MRI and no pain or functional problems.

If the cortisone is incompletely effective, we can look at a procedure referred to as pulsed radiofrequency or the dorsal root ganglion. The dorsal root ganglion is the part of the nerve that contains all the cell bodies of the nerves we are attempting to treat. Don’t mix pulsed radiofrequency with “Radiofrequency ablation”. Radiofrequency ablation heats the nerve up to 90 degrees and is trying to destroy the nerve. Pulsed radiofrequency alters nerve function and does not damage it. It is a needle-based procedure performed in a similar fashion to an epidural. A radiofrequency cannula is placed next to the dorsal root ganglion. The pulsed radiofrequency creates an electrical field about the ganglion and alters nerve function, only heating it to 42 degrees. It does this by upregulating anti-inflammatory factors, while down regulating inflammatory ones. This takes about 2 weeks to start to be felt but can have long term effects beyond 12 months.

If cortisone and pulsed radiofrequency is ineffective, we may need to decrease the compression of the nerve. This can be done surgically with procedures like microdiscectomies or laminectomies. Alternatively, non-surgical procedures like Percutaneous Plasma Discectomy (PPD) can be used. PPD’s can effectively decrease the size of the disc to decompress the nerve and relieve the pressure causing the pain.

Medication

A number of medications can be effective part of decreasing the irritation about the nerve root. We may use anti-inflammatories or medications such as amitriptyline, or duloxetine. Pregabalin (lyrica) is regularly prescribed but has been shown to be ineffective in most people with this problem. If it is not effective for you, speak to your doctor about ceasing it. (As a generally principle, if your medications are ineffective for you, talk to your doctor about ceasing them.)

Longer term if the nerve continues to create pain, it may have been injured. Over and above medications, injections and rehab for this, we will can consider neuromodulation as an option for managing the pain.

This instalment of the “Big 5 of lower back pain” covers disc and nerve pain. I have grouped them together as they are commonly confused as being the same thing, but put simply they’re not. That said, they regularly occur together, thus the confusion.

What is the difference?

From my point of view the main difference is that “Nerve pain” is really easy to diagnose, the treatment options are clear cut and I can get on with it. Disc pain, on the other hand, is hard to diagnose and much harder to treat and generates all number of frustrations for the both the person suffering and the person treating.

Diagnosis

Imaging for discs includes CT scans and MRI’s. CT’s can provide good information about bone in the area, facet joint arthritis and helps reassure you don’t have a cancer, but they aren’t overly useful for looking at discs. To look at discs we will use MRI’s. On MRI were are looking at disc height, dehydration, but more specifically Modic changes and annular tears or High intensity zones. Modic changes are an indication of the amount of inflammation and degeneration of the disc. Type I Modic change shows active inflammation in the bone on either side of the disc. It is a good indication that the disc is painful, (although, as with everything in medicine – unfortunately not always). Type II Modic changes are seen when the disc has progressed past an acute phase and into a chronic phase of degeneration. Once again, they are a reasonable (but imperfect) indication the disc is painful. In patients with Type I or II Modic changes, we can use a technique known as Basivertebral Nerve ablation to decrease the pain arising from the vertebra on either side of the discs.

The other strong sign we look for on MRI is known as an annular tear or a high intensity zone (HIZ). The annulus is the outer part of the disc. You can think of the disc as a jam doughnut with the jam in the middle being the “nucleus pulposis” and the dough the “annulus”. An annular tear is essentially as it sounds, a tear through the annulus (or dough part of the doughnut). Inflammation through the tear can be very bright on MRI, thus we refer to it as a high intensity zone. The presence of a HIZ on MRI is another good indicator the disc is likely causing the pain.

Even though we have all these “Indicators” that the disc may be the source of pain, it remains very difficult to diagnose. Because of this, treatments focusing purely on the disc have a lower success rate. To maximise the likelihood any of our disc treatments will be effective, we aim to be as sure a possible that the disc is the source of pain. We do this by talking what patients tell us, what we find on examination and MRI, we exclude causes such as facet and sacroiliac joint arthritis, and we can do low pressure provocation discography.

Low pressure provocation discography is a diagnostic technique where a special needle is placed into the disc believed to be causing the pain. A low pressure injection of some contrast dye is done to assess if the patients “normal” pain is reproduced. Depending on the pressure the pain comes on it can indicates whether the annulus or vertebra is causing the pain, and helps direct treatment. We also put local anaesthetic into the disc to assess if patients normal pain goes away after the procedure.

Treatment

We have an increasing number of options for treating discogenic pain. Those patients suffering intermittent sharp pain commonly respond to basivertebral nerve ablation. Those patients where the deep ache is the primary issue we can consider thermal annuloplasty and implantable devices such as L2 medial branch stimulators. Quite commonly we will combine these to maximise pain relief achieved by the patient. Following any of these procedures patient will proceed into a rehab programme aiming to recondition the lumbar spine.

Discogenic and nerve pain

As we mentioned above. Nerve root pain and disc pain can occur together, but it isn’t a necessity. A disc protrusion can compress a nerve and the nerve will cause the pain, but the disc itself may not actually be painful at all. That said, low back pain arising from discs is the most common cause of pain occurring in about 30% of people. It will produce a constant deep ache and intermittent sharp pain. The pain can be central or to one side in the back, and like the other “Big 5 causes of low back pain” can radiate down the back your legs, or into your thigh. It tends hurt when you stay in one position for any period of time, this includes sitting, standing and lying. Making it very difficult to escape. Many patients find they get pain with doing things like brushing their teeth, the dishes or coughing and sneezing. Although, none of these symptoms are diagnostic.

hip joint pain

Hip joints are responsible for approximately 15% of back pain. The pain from hip joints commonly radiates to the buttock, and although buttock is technically not back, the commonly gets caught up in the overall presentation. People suffering hip pain commonly have associated groin pain. Groin pain is by far the most common presentation of hip joint arthritis. People have significant pain with crossing the legs, putting on the shoes, and getting in and out of a car. As the pain gets worse people develop a limp and have difficulty with sitting. Other than osteoarthritis, hip joints can cause pain due to labral tears and inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis.

Diagnosis

Hip joint osteoarthritis is diagnosed based on history and examination findings. We commonly then proceed to an x-ray which if arthritic, will show joint degeneration. If it is unclear, a diagnostic injection of local anaesthetic plus or minus cortisone can be done to confirm the patient's pain goes away when treating the joint. Although Cortisone generally lasts only a short duration.

Over many years we have trialled multiple injectable interventions such as platelet rich plasma, autologous conditioned serum and hyaluronic acid have failed to achieve significant long-term relief.

Management

Unfortunately, that does not leave many options for managing osteoarthritis of the hip, however, hip joint replacement is quite possibly the best operation Western medicine has to offer. For those patients who are on waiting lists we used techniques such as injections of the articular branches of the femoral and obturator nerves, plus or minus epidural injections over the nerve root supply to hip as a means of controlling pain until the patient is able to have the joint replaced. We can combine this with pulsed radiofrequency or thermal radiofrequency to prolong out the effect.